A backbone of Automotive Electronics

More than half a century of Bosch gasoline injection Jetronic

It was the October 2006, when Dr. Heinrich Knapp appeared at the entrance to the exhibition on Bosch history, close to the Stuttgart-Feuerbach plant. The retired engineer handed a small – but extraordinary – scrap of paper to an astonished Bosch associate.

It was the original schematic for an electronic gasoline injection system, which he himself had drawn up in 1959. He said he wanted to donate it to the Bosch archives.

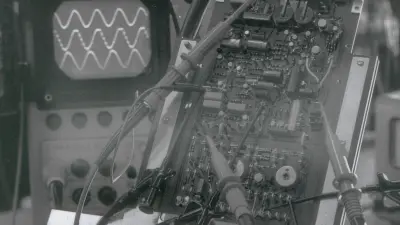

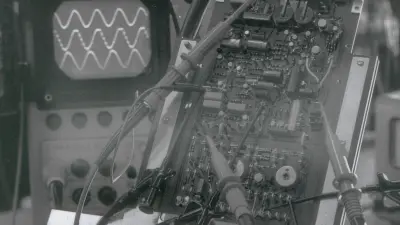

A physicist, Knapp had been one of the key members of this pioneering project to use electronics to control fuel injection. He had been assigned the task of developing the first prototypes in 1959. For this purpose, Bosch bought a Mercedes-Benz 300 as a company car and converted it into a test vehicle for electronic gasoline-injection systems. Before taking the car in for servicing, Knapp revealed when he handed over the drawing, the vehicle was refitted with its original carburetor, so the manufacturer would not suspect what Bosch had in mind.

Try, fail, hide

The official task assigned to the Hong Kong office that was opened in fall 1986 was to expand business in this East Asian economic center, but also During the 1950s and ’60s, it was still hard to convince customers in the automotive industry of the merits of electronically controlled technology. Electrics, mechanics, hydraulics, and pneumatics were the cornerstones of the reliable technology Bosch supplied to the automotive industry at that time. This applied equally to generators in buses, plow-lifters in tractors, power-window units in sedans, and ignition contacts in mopeds. When it came to electronics, the experts at most European automakers were skeptical, even though the technology was well-established in products such as radio equipment and televisions.

The use of electronic components in cars was a bold move, but there was scope for things to go wrong. For instance, when the U.S. Chrysler Corporation installed the Bendix Corporation’s Electrojector, an electronically controlled gasoline-injection system, in its Chrysler 300 sedans, the system turned out to be so unreliable in everyday use that all the sedans had to be refitted with conventional carburetors. Despite its almost nine-year head-start over Bosch, Bendix’s system failed. This experience was invaluable for Bosch. Using each other’s patents, the two companies were able to develop their injection-technology expertise. However, Bendix subsequently stopped work on its own solution.

“A little too unorthodox”

During the early 1960s, the United States first recognized the need to combat increasing air pollution. The summer smog in Los Angeles presented a major health hazard, and in 1963 this gave rise to the federal Clean Air Act, one of the world’s first environmental protection laws.

And this is where Bosch came into play. The subsequent announcement of the even stricter Air Quality Act for automobiles from model year 1968 on, i.e. for vehicle sales starting in the late summer of 1967, presented many automakers with a problem.

Prior to this, for example, Volkswagen AG’s range had included its successful type 1, known as the Beetle in the United States, which was then joined by the somewhat larger type 3. The type 3 was fitted with the same four-cylinder boxer engine as the Beetle, but with greater displacement. Using a conventional carburetor, the new pollutant emission standards set by the Clean Air Act would have been unachievable with this higher-displacement engine – the type 3 would not have been approved by the U.S. authorities.

Prototypes

Bosch was already in contact with VW at this point and was also able to demonstrate its first test vehicles, which were almost production-ready – a Mercedes-Benz 220 SE and a VW 1500. Hermann Scholl played a key role in the development of electronic gasoline-injection systems from 1962 on. Now the honorary chairman of the Bosch Group, Scholl recalls: “In 1964, our customer Volkswagen was initially as skeptical as pretty much every automaker that we had tried to convince of the merits of our innovative injection system.”

It was a little too unorthodox and at that point, no similar mass-produced system had yet proved its worth. As Scholl recalls, “automakers had to take a certain risk.”

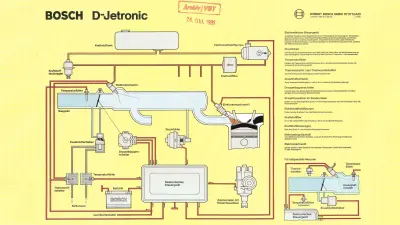

The launch

On September 14, 1967, Bosch unveiled the electronically controlled “Jetronic” at the International Motor Show (IAA) in Frankfurt. It was initially marketed in the United States, owing to the strict new emissions standards in the important Californian market. It took a while for automotive customers in Europe and Asia to follow suit. A Jetronic-equipped VW 1600 debuted in Germany in June 1968, but the mark-up on the car’s basic 6,000 price tag was a hefty 600 German marks. Not surprisingly, very few customers ordered the car with this technology, despite the reviews praising the way it improved engine operation. Emissions standards in Europe were yet to cause problems for engines featuring conventional carburetor technology.

However, other manufacturers identified two additional key benefits of Jetronic – lower gasoline consumption and the potential for boosting engine performance. This led automakers such as BMW, Citroen, Jaguar, Lancia, Mercedes-Benz, Opel, Renault, Saab, and Volvo to fit this Bosch technology in some of their top-of-the-range models from 1969 on.

The repercussions

Some customers in the automotive industry were not yet sure whether this was really the way forward. Even at Bosch, there were proponents of mechanically controlled injection systems. To be able to supply both kinds of technology, the successor systems developed by Bosch included K-Jetronic, a mechanical counterpart to the electronic L-Jetronic. Both debuted in 1973. In the years that followed, this led to something of an inter-departmental tug of war, with considerably more mechanical systems being sold at first. In the end, electronic gasoline injection won out due to more stringent emissions legislation worldwide.

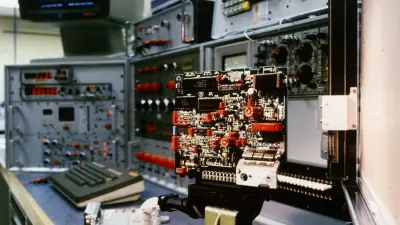

This legislation meant that catalytic converters were needed to reduce emissions, and this in turn called for additional electronic systems such as the lambda control. The latter regulates the ratio of air and exhaust gas in a combustion engine, ensuring that fuel is burned as cleanly as possible. Mechanical systems were only able to achieve this, if at all, with increasing effort, which soon grew out of hand. The inclusion of both injection and ignition systems in the Motronic digital engine management system, which Bosch unveiled in 1979, finally gave electronics the upper hand in air-fuel mixture technology.

Successors

Jetronic’s successors can also be found in contemporary cars. This pioneering technology thus prepared the ground for new standards. What’s more, Jetronic was the starting shot for the success of electronic systems, without which automotive electronics would be nowhere near as significant today.

Drivers’ confidence in electronic management systems such as common rail, ABS, airbag control, and parking assistants would certainly not have been won so quickly without Jetronic paving the way.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz