Acting with foresight and tolerance

What we can learn from Robert Bosch

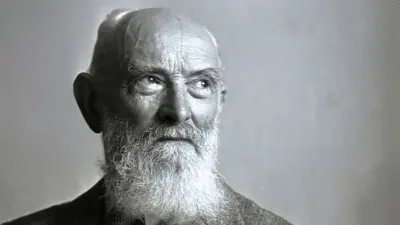

Robert Bosch was an entrepreneur who was not afraid to stand up for his convictions in business, society, and politics. He used his prominent position as a business leader to promote conciliation and understanding.

Robert Bosch traveled to Berlin on November 5, 1918 – a few days before Germany surrendered and the first world war came to an end. The mood was volatile. The soldiers and war-weary population had more than just hunger to be angry about. The old political system with its impervious hierarchies was about to collapse. A revolution threatened to radically change the economic order. Old elites and revolutionaries were irreconcilably divided on political and economic issues. Bosch knew that a Russian style revolution would destroy his life’s work and that the only way forward was to act calmly and include all sides. But he also knew that change was essential.

Bosch regarded tolerance, mutual respect, and pragmatism as cornerstones for implementing economic and social change. Conciliation and understanding were always behind his commitment to business and society. He was 57 and had been a successful entrepreneur for 30 years. His experiences and reflections had laid the foundations for this.

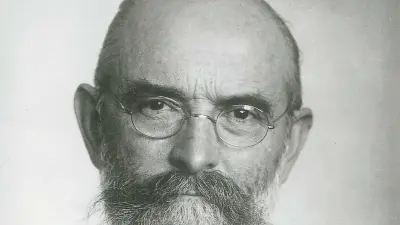

The pragmatic and tolerant approach that typified him as a business leader attracted the interest of politicians. The new state that emerged from the post-war upheaval was faced with establishing a new economic order in Germany at the beginning of the 1920s — one that reflected blue-collar workers’ strong desire for co-determination. This prompted the political decision makers to establish the “Provisional Imperial Economic Council”. The state government of Württemberg appointed Robert Bosch to the Council, which comprised various stakeholders and was tasked with preparing draft legislation. There he joined a group of independent experts and was assigned to the Social Policy Committee. Looking back, he took a positive view of the Economic Council “because it forced employers and employees to sit together at one table for the first time.” Ultimately, actual results were needed, not constant ideological battles.

The idea of establishing works councils in Germany was being discussed at the same time. How much of a say elected employee representatives should have in the running of a company was a fiercely debated issue. Most employers wanted to prevent this interference in their interests by any means. Bosch, however, advocated bringing employers and employees closer together. He knew that, within a company, it is necessary to achieve “the broadest possible degree of mutual trust”. He was not afraid to work together with works councils provided that both sides did not lose sight of their boundaries or their common goal, the company’s successful continued existence. He knew that “employer and employee are equally dependent on the fate of their company.”

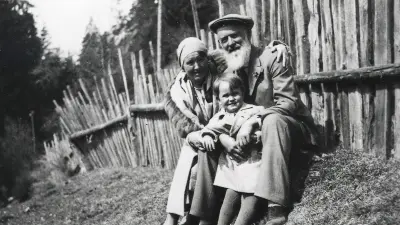

His approach sometimes made him an enemy of industrialists and employees alike, but he always remained true to himself. As a result, he became a role model for young, modern entrepreneurs. His position as an international entrepreneur also enabled him to make contacts among business leaders around the world. He took care to seek out like-minded people. In the 1930s he and Louis Renault, head of the automotive manufacturer of the same name, shared the belief that a united Europe needed to be created as a strong economic region without trade barriers, with France and Germany as the driving forces. Even more importantly, they hoped that this would prevent future wars in Europe.

He also reached out to Henry Ford, the forward-looking US businessman, to try and convince him of the idea of a united Europe. In 1935 he wrote Ford a noteworthy letter in which he first addressed what the two had in common: “I suppose that you and I are two of the oldest industrialists in the world who have been engaged in applying science to industry.” His view was that a European Economic Area should be created to protect the peace — and he asked for Henry Ford’s help in realizing this goal. His letter concludes: “As an industrialist, I feel we should not allow the politicians to have it all their own way, we should do something to create a healthy and sound public opinion so that these problems may be solved in a commonsense way, and it is for this reason that I ask you to interest yourself in the matter.” Unfortunately, his letter appeared to go unanswered, and history shows that Bosch’s efforts were unsuccessful. A few years later, the world once again found itself at war. The time for Robert Bosch’s ideas had not yet come. It was not until after his death that a European Economic Area was formed in the 1950s, and went on to become the European Union. To this day, the EU has brought freedom and prosperity to the region and proved with hindsight that Bosch’s beliefs were right.

“The highest principle should be: Never forget your humanity, and respect human dignity in your dealings with others.”

His tolerant and respectful approach as a business leader who had the courage to tackle social issues has not lost any of its significance to this day. Especially in changing times, when established structures are being questioned and fierce debates about the right way forward for the economy are taking place on all platforms, his words from 1920 are more relevant than ever: “Anyone who seeks his way in life with integrity and always remains true to his conscience deserves our respect, whether he be with us or against us. It would be unwise to expect that in the future everyone will simply be content with what they are offered. There will be struggles in the future, too, but they should be honest, decent struggles.”

Author: Christine Siegel