New paths to a global presence

Bosch goes international at the end of the postwar boom

Robert Bosch GmbH can look back on a long history of internationalization. The first sales office outside Germany opened before 1900, the first manufacturing plant abroad opened in 1905. However, the wave of internationalization that began in the 1960s and 1970s is of notable strategic importance, as it saw the company opening up the U.S. and Asia in particular and reducing its dependence on the German and European markets.

A perfect world on demand

Following the collapse of international structures after 1945, the company launched a major campaign to become a global player again with branches on all continents. But this mission was a marathon. In 1965, Bosch was still generating around 66 percent of its total global group sales in Germany. When it came to the original equipment business, the area of automotive technology that generated the strongest sales, Bosch was heavily dependent on German car manufacturers and very poorly positioned internationally. In addition, the company was not prepared for the sharp rise in manufacturing volumes from international players in Japan.

A shock with consequences

The business climate in Europe took a major downturn in 1965. Sales drivers such as injection systems slipped into the red, and inventories grew twice as much as planned. Bosch reacted quickly by reducing inventories, stopping investments, and imposing a hiring freeze. Clearly, achieving an international balance in manufacturing and sales was becoming increasingly urgent. Bosch had already established manufacturing facilities in Brazil, India, and Australia in the 1950s to supply regional customers. Yet despite modernization of the company and international manufacturing operations, the complex and unpredictable economic conditions were causing more and more problems for Bosch.

Balance through a global market

It therefore made sense to establish additional markets outside Germany and manufacture locally where large quantities were required. The U.S. and Japan are two prominent examples of the successful expansion of the “local for local” strategy.

In the United States, all Bosch property was expropriated after the second world war. The new Bosch subsidiary founded in 1953 was only allowed to use the name “Robert Bosch” or “Bosch Germany.” At the end of the 1960s, the U.S. was the world’s largest market not only for automobiles in general, but for heavy commercial vehicles as well. As the diesel business was traditionally the strongest at Bosch, breaking into the American market was the obvious choice.

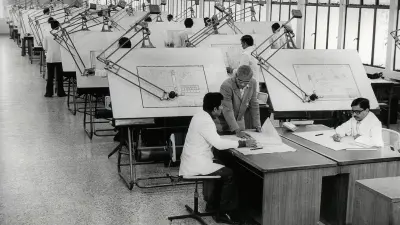

Manufacturing and trademark rights in the U.S.

To be closer to potential customers, Henry Schirmer, president of the U.S. Bosch subsidiary, decided in 1966 to move from New York to the town of Broadview, Illinois. Business agreements in the field of diesel technology were concluded with original equipment manufacturers such as International Harvester and Deere & Company. The technology supplied from Stuttgart usually still had to be adapted to customers’ individual needs, and so the Broadview site was further expanded for this purpose. The company then decided to serve the U.S. truck industry with its Charleston manufacturing site in South Carolina, which was completed in 1973.

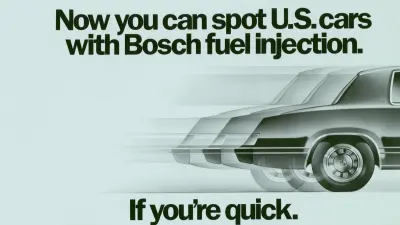

Electronics business pays off

Breaking into the high-volume car business with the “big three” — General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler — took longer, however. It was Bosch’s electronic systems that led to the company’s establishing itself permanently in the passenger car sector. This is because strict emissions legislation in the U.S. provided Bosch with an extra boost, particularly in the area of electronic gasoline injection systems, as these helped significantly reduce emissions. Step by step, Bosch successfully challenged the market power of the traditional U.S. suppliers by offering the latest in automotive technology.

As a result, the company was already established as an original equipment manufacturer in the U.S. when, after decades of disputes, it finally regained all trademark rights for use in the U.S. in 1983. The groundwork had been laid, but it was this final step that provided tremendous relief: there were now no longer any competing U.S. products under the Bosch name that could jeopardize Bosch’s original equipment business.

The rising importance of Asia

From the 1960s onward, Asian automotive markets were an increasingly important focal point for Bosch as it sought to offset the flagging European car market through international expansion. Long before China and ASEAN became viable markets for Bosch, it was the up-and-coming Japanese automotive industry that first caught the company’s interest. In 1962, Toyota, Japan’s largest automaker, manufactured around 210,000 cars; this was not even one-fifth of the vehicles that rolled off the VW Group’s production line. But then, ten years later, Toyota produced over two million units — almost 50 percent more than the VW Group.

Partnerships for a stronger presence

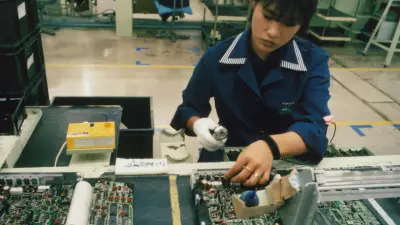

This development led to one of the company’s most challenging tasks. At that time, Bosch had few market opportunities for all business units in Japan — there was neither great demand for power tools for DIY enthusiasts, nor was it possible to certify home appliances for the Japanese market at a reasonable cost. This extremely restrictive market was also an almost insurmountable barrier for automotive suppliers outside Japan. The only access options were modern technologies that Bosch, but as yet no Japanese manufacturer, could offer.

The successful Jetronic gasoline-injection system was the door opener for Bosch, and in 1973, the company signed a contract with a Japanese consortium to create a joint venture called Japanese Electronic Control Systems, or JECS. That set the precedent for another joint venture, Nippon ABS Ltd., which emerged 12 years later. With it, Bosch took the antilock braking system it had introduced in 1978 and made it a commercial success in Japan. This put Bosch’s reputation as a supplier to the Japanese automotive industry on a solid footing.

Two of many strong markets

The U.S. and Japan are just two of the markets that Bosch reopened, albeit the most important ones at the time. From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, Bosch also invested worldwide in international acquisitions and production facilities or completely new manufacturing sites in Brazil, Mexico, India, South Africa, Belgium, Spain, Malaysia, and Türkiye. Bosch had once again become a global supplier, increasing its share of international sales from 35 to 55 percent between 1965 and 1975.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz