Ideas to save the future

A look back in history

Over time, things rarely remain the same for long at a company like Bosch. A business has to develop tools to master challenges such as crisis situations, technological paradigm shifts, and market needs. More than 90 years ago, bright minds at Bosch came to this very conclusion. They developed strategic approaches that remain valid to this day for helping the company advance.

“Robert Bosch A.G. is currently experiencing difficulties which are not likely to improve soon. Our company not only will surmount these difficulties, but also has the strength within it to regain its former standing and consolidate it anew.”

As the company marked its 40th anniversary in 1926, Robert Bosch had a message for his staff: keep looking toward the future — and keep going. A severe crisis in the automotive industry had plunged Bosch into dire straits, forcing it to lay off half of its nearly 14,000 associates.

The well-trained skilled workers that the company let go were in short supply once things started to turn around. Yet the next downturn was waiting just around the corner as the crisis-plagued 1920s drew to a close. In October 1929, “Black Thursday plunged the global economy into a deep recession, dragging the automotive industry and its suppliers down with it.

Response to the crisis

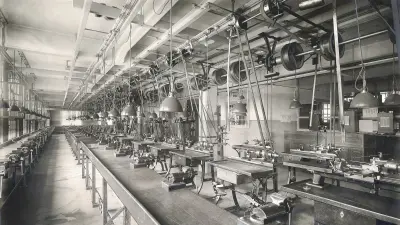

Bosch responded in 1930 by setting up a new department, the office of technical management (BTH3). Its job was to find new business ideas that could be quickly rolled out and would make Bosch less dependent on the automotive industry in order to keep fluctuations in the number of associates low. Robert Bosch took his responsibility for his associates very seriously, right from the start, and found it hard to cope with the need for mass layoffs. Because the corporate culture was a different one, BTH3 got to work quickly finding alternatives that were designed to help lessen the impact of the crisis. Developing entirely new products, or re-engineering existing ones, was not an option. Given the precarious situation, the company lacked the time to do so.

Five proposed solutions

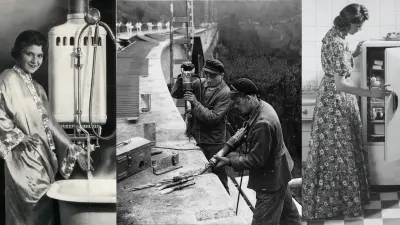

As a result, Bosch placed its hopes on five strategies, which BHT3 summed up as follows in a report published in 1940: take up and develop outside ideas, acquire patents, take over parts of other companies, take over entire companies, and issue licenses in Germany and abroad. The acquisition of Junkers’ thermotechnology division in 1932 was one example, as was the issuing of licenses for production in Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, and France between 1928 and 1939. Working with partners outside Germany provided many advantages. The partners gave Bosch access to the market. What is more, sales of other products benefited from the company’s higher profile. Sharing technical and organizational expertise with international partners turned out to be a tremendous enrichment for Bosch’s business.

Focus on research and development

At the same time, the report also stated how important it was to plan for the future while continuing to develop and enhance products even during phases of economic recovery, when production was running at full steam and there were almost too many orders to handle. In its 1940 report, the BTH3 proposed a “research corporation” that would be independent of the company’s day-to-day business operations and would have their own production facilities for innovative new products and products to be tested. The ideas were met with keen interest at Bosch and would eventually prove to be reliable methods for successfully surviving even the worst economic crises.

“Not invented here”

A look at Bosch’s recent past reveals that many of these approaches live on to this day. Despite becoming more global in scale, their core substance remains the same, as many examples from the past five decades illustrate. One decisive factor is overcoming the reluctance to embrace innovations that did not originate from within the company, a phenomenon often referred to as “not invented here.”

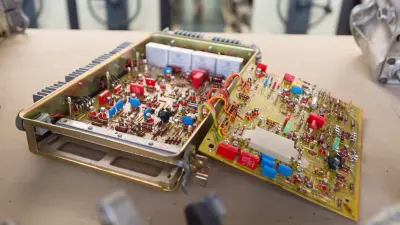

Doing so means acknowledging that it is sometimes better to benefit from the expertise of others rather than always having to one-up the competition. For example, Bosch developed electronic gasoline injection, which hit the market in 1967, in a process known as “cross licensing.” In exchange for providing knowledge and expertise to a U.S.-based competitor, Bosch received access to its intellectual property. It was this approach that enabled Bosch in 1967 to launch the world’s first successful electronic gasoline-injection system to be produced on an industrial scale. Within just a few decades, the technology would become standard in the automotive industry.

Relying on external expertise

There are also ways to make even more extensive use of the capabilities of other technology leaders. In new business fields, this approach may mean allowing the company to focus on what it does best and choosing to source components or subsystems from specialists. One such example is the promising new field of hydrogen-based fuel-cell technology. The technology makes climate-neutral energy generation possible — a field in which Bosch aims to play a leading role, both at stationary power plants and in vehicles. However, Bosch can only help set the pace of innovation if it finds an appropriate way to contribute to value creation. That is why Bosch has chosen the Swedish PowerCell to develop stacks, the core element of generating electricity using hydrogen. Developing them without a competent partner would have cost precious time in competing for a leading role in hydrogen technology. The focus is on system competence when Bosch then obtains and amasses expertise in all other areas covered by the new business unit, often relying on its own experts and proprietary technical knowledge.

Binding knowledge and experience to the company

Often, though, future megatrends and the need for basic know-how that has to be further developed within the company often make acquisitions essential. In 2008, for example, Bosch took over Software Innovations GmbH. At the time, the company was a leading player in the field of software solutions for the internet of things. Such solutions play an important role in Industry 4.0 and are gaining importance in the field of mobility as well. They enable communication between machines and systems that are capable of preventing downtime and increasing productivity in manufacturing — all while saving resources in the mobility and consumer goods sectors or increasing safety and practicability.

After the acquisition, Bosch quickly transformed the new operating unit into a center of competence that is active in various divisions at Bosch. Today, it is part of the Bosch Digital operating unit.

Bosch was already practicing methods like these more than 90 years ago. Some of the ideas will be as relevant in the future as they already are today.

Authors: Christine Siegel / Dietrich Kuhlgatz