Robert Bosch’s commitment to international understanding

“Only mutual understanding can create a viable relationship”

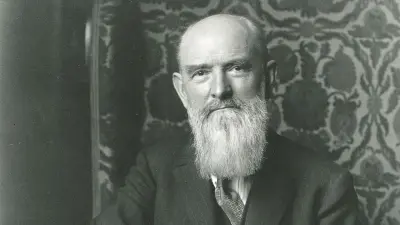

For Robert Bosch, relationships across national borders — whether personal or business — were a matter of course. Without global partnerships, he certainly wouldn’t have risen so quickly to his status as a successful major entrepreneur. After the first world war, he campaigned for international understanding and supported Franco-German rapprochement in particular.

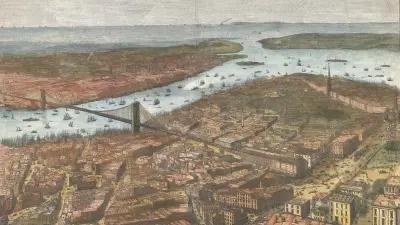

Presence in many countries

After completing his apprenticeship, Robert Bosch traveled for a few years, working in the U.S. and the U.K. As an entrepreneur, he pursued the internationalization of his business early on. He set up his own branches in London, Paris, and New York and concluded agreements around the world to distribute his products. In the 1910s, Bosch generated over 80 percent of his total sales outside Germany. He observed the escalating international tensions with concern, as unstable foreign policy conditions would not only impair economic growth, but also hold back technical innovations and developments.

With the outbreak of the first world war in the summer of 1914, the worst-case scenario became reality. International business came to a standstill. Even more serious for Robert Bosch was the suffering that the war inflicted on people. He took steps to alleviate immediate hardship and was able to donate generously, thanks to his financial resources. As the war progressed, the company also produced war materiel. At the end of 1916, Bosch decided to donate all the profits he had made from the war to the construction of the Neckar Canal, as he didn’t want to become “one penny richer as a result of this war.”

Policy of rapprochement

As a result of these efforts, he took on an increasingly public role and stepped up his socio-political activities after the war. At the company headquarters in Stuttgart, he had the support of a group of board members whom he trusted completely and who took care of day-to-day operations. This freed up time for Bosch to forge links with politicians, and he often traveled to Berlin to do so. As an entrepreneur who had built up and maintained international partnerships over many years, Bosch was deeply interested in fostering understanding between nations. He supported several initiatives both financially and through his active involvement.

“German Michel must marry French Marianne.”

The relationship between France and Germany was particularly close to Robert Bosch’s heart. He saw the rapprochement and reconciliation of these two neighboring countries as the first, most important step on the way to creating a united and peaceful Europe. To get closer to this goal, he was more than willing to promote different movements and approaches. In principle, he considered all those working toward a united Europe to be worthy of support. Although he could not and did not want to “give contributions to all and sundry,” he had to “be pleased that a wide variety of interests are recognizing that uniting Europe is the goal.”

Ideas for a united Europe

Robert Bosch became a member of the Committee for Franco-German Understanding and the Paneuropean Union. While the committee, with branches in Paris and Berlin, mainly pursued economic interests and promoted bilateral industrial alliances, the Paneuropean Union aimed to unite Europe politically. The movement, initiated in 1922 by the Bohemian philosopher and writer Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, met with great interest in intellectual circles. The idea of the Paneuropean Union, which was to establish a Central European confederation of states and a common economic area, mirrored Bosch’s vision for the future of Europe. He made several donations to both associations and was also involved through his network as a major industrialist.

Securing peace and global economic frameworks

Robert Bosch used his contacts with entrepreneurs, politicians, and acquaintances from public life to gain further supporters and sponsors for Franco-German friendship and a unified Europe. He wrote to Louis Renault in December 1931: “However, I was told that you also expressed the opinion — and I am extremely pleased about this — that France and Germany must reconcile as an act of understanding for peace in the world. I would like to reiterate that I am deeply moved to know that you hold this point of view.”

At the same time, he was aware of the business implications of the movement toward understanding. “I hope,” he wrote to a friend on January 3, 1933, “that [...] in time, an intimate union will develop between France and Germany. This will be an opportunity to turn Europe into a large economic bloc that can participate as an equally strong contractual partner in future disputes and discussions about a global economy.”

The long road to international understanding

Even when the political possibilities for an understanding collapsed with the beginning of National Socialist rule in Germany on January 30, 1933, Bosch persevered in his efforts. He continued to try to influence politics and built upon the willingness in both countries to overcome hatred.

However, his optimism was increasingly mingled with resignation. In his final attempts at peaceful coexistence, he initiated a Franco-German vacation exchange program for children in the summer of 1934 and invited French and German war veterans to a meeting in Stuttgart in 1935. In the end, he had to admit to himself that his efforts had failed and that there was (still) no way to achieve international understanding.

In the 1950s, however, it was possible to build on the ideas that Robert Bosch had supported. The rapprochement between France and Germany led to economic and political cooperation in Europe. This in turn led to a unification process that led to the establishment of the European Union.

Author: Bettina Simon