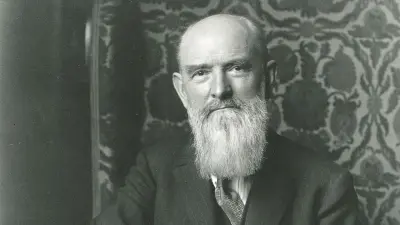

The democrat Robert Bosch

What makes someone a “democrat”? Common definitions describe a democrat as someone who accepts decisions that have been made democratically, even if they don’t agree with those decisions. A democrat is also tolerant and fair in their dealings with political opponents and is committed to the common good. Going by this definition, Robert Bosch was a democrat in the best sense of the word.

Principles established early in life

Robert Bosch’s democratic roots were planted at the time of his birth in 1861, as his father Servatius was already a staunch advocate of democracy. His views, in turn, were shaped by the ideals of the Enlightenment. As a Freemason, Servatius embraced the five principles of that organization: liberty, equality, fraternity, tolerance, and humanity. He tried to put these into practice in everyday life and passed them on to his children.

Experiences with the “rule of the people”

And he succeeded. When Robert Bosch traveled to the U.S. at the age of 23 to gain work experience, he chose his destination carefully: “I went to America [...] as a young democrat, which I was by dint of my upbringing and following the example set by my father and older brothers.” His own experience had exposed him only to the monarchy and inadequate electoral system in Germany, so he wanted to see how things would be in a liberal democracy in which the people, and not a monarch, ruled. He was disillusioned to realize that the U.S. of the late 19th century didn’t meet all the conditions for this. Robert Bosch felt a lack of “the cornerstone of justice — equality before the law.” In many places, Black people and Asian immigrants were left off the equality agenda.

Solidarity — an essential component

In addition to the freedom that defines a democracy, the social aspect was also important to Robert Bosch. The ideals of equality and solidarity shaped his thinking early on. During his time in the U.S., he joined a trade union that propagated these ideals. However, when he suggested a kind of unemployment benefit at a meeting that the members should finance, his words fell on deaf ears. He remembered this episode with disbelief almost four decades later as he was writing his memoirs. In them, he also further detailed the social component of his political convictions: “I was brought up a democrat. I had worked as a mechanic and grew up among the people. The socialist movement, which began with such force and confidence in the 1870s, exerted a powerful attraction on me.”

Balance through justice

Robert Bosch believed that people’s being born into wealth or poverty, and not having equal opportunities at the start, was a great injustice that needed to be rectified. However, as an entrepreneur, he gradually moved away from the idea of genuine socialism, which he had cultivated in his youth and which went as far as the socialization of property. But his feelings regarding the social component remained. In 1921, he noted: “At any rate, I have always voted socialist to this day. I was prevented from joining the party by the fact that, as an entrepreneur, I would only have been regarded as an exploiter by my comrades, and then the struggle increasingly became a class struggle. An entrepreneur with a social conscience simply got in the way.”

Education is the key

Nevertheless, Robert Bosch stuck to his convictions and tried to put them into practice. He remained a great supporter of equal opportunity. Where he saw deficiencies, he tried to remedy them. This was particularly evident in his promotion of education. For him, it was the key to an equal society. In many initiatives, his financial support helped gifted children who would have been denied a higher education due to their social background. He also promoted public education, because: “I completely agree [...] that the basis for a prosperous state is the best possible general education.”

Tolerance

Accepting a decision that has been reached democratically, even if it contradicts one’s own ideas, is fundamental in a democracy. Robert Bosch took a critical view of some of the political decisions made during the Weimar Republic, but he accepted them nonetheless. He also repeatedly advocated fair treatment of those with different opinions. Intuitively, he knew that intolerance and insisting on one’s own opinion without considering the other person’s arguments would achieve nothing: “Those who seek their path uprightly, always responsible to their conscience, must not be denied our respect, whether they walk with us or against us. It would be unwise to demand that, going forward, everyone should simply make do with what they are offered. It will still be a struggle in the future, but it should be an honest, upstanding struggle.”

Maintaining human dignity

With this fundamental democratic attitude, it’s hardly surprising that Robert Bosch had no sympathy for the Nazi dictatorship. His reaction to the silencing of inconvenient political opponents through reprisals and the inhumane treatment of the Jewish population and other minorities was one of incomprehension and horror. One of his principles was: “Never forget your humanity, and respect human dignity in your dealings with others.” He helped where he could and supported Jewish associations financially, for example. The political environment of the time was very difficult for him, as was the increasing involvement of his company in Germany’s rearmament efforts. This area of tension caused the democrat Robert Bosch many a dark hour in the last years of his life. His legacy is his lifelong efforts to help people develop a basic democratic understanding based on the “recognition of the rights and merits of others.”

Author: Christine Siegel