A history of how Bosch’s expertise turns third party ideas into viable products

A common goal

Often, a good idea alone is not enough to develop a new product. The trick is to make it robust, powerful, and efficient so that it can be mass produced. Sometimes, it also takes a partner to deliver the decisive spark of inspiration. Time and again over the course of its history, Bosch has latched onto ideas and helped make them a success.

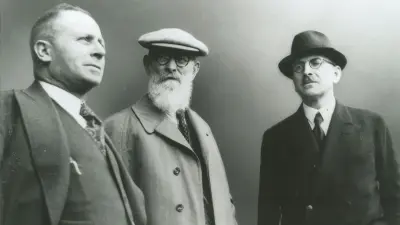

The idea was ingenious. In his experimental workshop, Ernst Eisemann had developed an innovative new power tool. Featuring a drive that was integrated into the handle, his invention no longer needed a suspended, external motor. However, with its substandard insulation and tendency to heat up quickly, the tool was also a fire hazard. This was where the Bosch engineer Hermann Steinhart came in. Not someone to give up easily, he found a way of insulating the tool to make it safe. Reborn as the “Forfex” haircutter, and thanks to some clever marketing, the tool became a best seller in 1928. Without Steinhart’s help, Eisemann’s stroke of brilliance might have been tabled indefinitely. The secret was teamwork – as so often in Bosch’s history.

Back in 1897, Robert Bosch’s factory manager Arnold Zähringer acted on a customer request and reengineered a magneto ignition device so that it could be installed in cars. While the fundamental technology behind the product was not Bosch’s idea, Zähringer’s modification was the breakthrough for safe ignition in the burgeoning automotive sector. Although the idea came from outside the company, the customer knew exactly who to turn to. Bosch was renowned for its focus on quality and vast technical expertise, as well as for its refusal to be deterred by initial setbacks.

What is more, Bosch had considerable manufacturing expertise. At the turn of the 20th century, the company’s associates were still making goods one at a time. However, Robert Bosch made sure that this work was done with modern tools and in line with the latest standards.

“It was never my ambition to actually make something myself. I liked to let others design, and I liked to let them earn well, too. My only ambition was to be able to say that whatever is made in my name must be both first-class and faultless.”

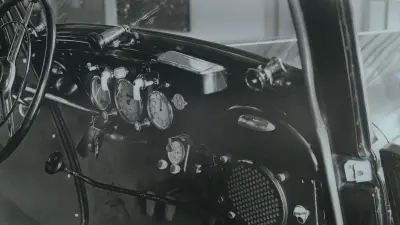

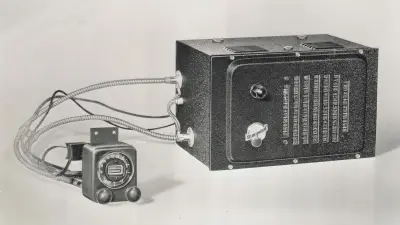

Alliances with strong partners also worked in the other direction. While it is nothing unusual today, listening to music or the news while driving was very uncommon at the start of the 1930s. Bosch had started developing a car radio, but found itself unable to solve certain problems related to radio technology. As a result, it approached Ideal Werke, later known as Blaupunkt, a company with extensive experience in the field. Bosch itself contributed its specialist knowledge in automotive electrics, as well as its manufacturing expertise. The partnership gave birth to Europe’s first mass-produced car radio.

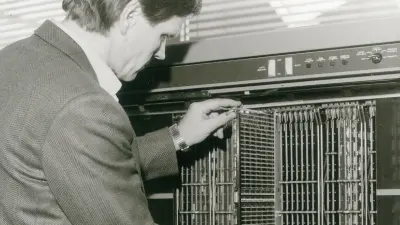

Some 40 years later, Bosch’s experience in electronics prompted its customer Daimler-Benz to put out feelers. With cars capable of ever greater speeds, locking wheels were a recurring cause of serious accidents during emergency braking. Daimler was therefore interested in the “antilock system for vehicles” developed by the German company Teldix GmbH. While the product itself worked, the electronics on which it depended was anything but durable. Bosch, however, possessed vast expertise in the field of electronics. After Daimler had brokered contact between the two companies, Bosch acquired a stake in Teldix, and the two companies started working on the antilock system together. The result of their joint efforts, the ABS antilock braking system, debuted in 1978. Over time, it became a standard feature, and today’s cars would be inconceivable without it.

There are many more such examples throughout Bosch’s history, including the development of the safety natural-gas ignition switch in collaboration with Junkers around 1930, and the further development of common-rail technology with the Italian partner Elasis in 1997.

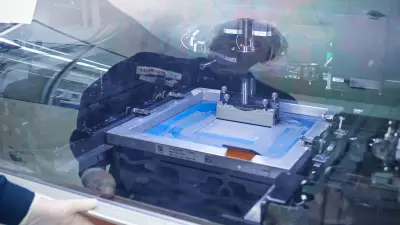

In 2018, Ceres Power, a developer of stationary fuel cells, caught wind of Bosch’s manufacturing expertise. Undoubtedly, Bosch’s emphasis on sustainability and resource conservation in its business operations also played an important role. Ceres’s idea helps protect the environment, making it an ideal fit for Bosch. Stationary fuel cells offer an eco-friendly way of meeting the rising demand for energy, especially in major cities. Phil Caldwell, the Ceres CEO, sums up the advantages of the partnership: “Combining innovative Ceres technology with Bosch’s manufacturing expertise made it possible to create pioneering stationary fuel-cell systems that will help overcome the global challenges of the move to alternative energies.”

Most recently, in 2021, there is the example of the mobile fuel-cell partnership with China’s Qingling.

While the names may have changed, teams like Ernst Eisemann and Herman Steinhart have always played a vital role and will continue to do so. Yet success is not solely a matter of individual brilliance. Sometimes, it is the creative solution of a department or an entire company that, in collaboration with Bosch, makes innovative technology accessible for a wide range of customers.

Author: Christine Siegel