The hidden engine: How applied mathematics powers a world “Invented for life”

Bosch Research Blog | Posted by Michael Schick and Uwe Iben, 2026-01-23

Have you ever wondered how a modern car can autonomously brake to prevent a collision? How a factory can predict its own maintenance needs, or how a simple power tool can be engineered for perfect balance and minimal vibration? At Bosch, where technology is “Invented for life,” the answer is not just brilliant engineering. It's the silent, indispensable engine running in the background: applied mathematics.

What is “applied mathematics”?

At its heart, applied mathematics is a bridge connecting the logical and abstract world of mathematical theory with the complex reality of industrial use cases, often also addressed as “industrial mathematics” to emphasize the challenge to solve real, tangible problems in industry. At Bosch, this means modeling, simulating, predicting, and optimizing the products and systems that millions of people rely on every day.

Think of it like this: a university professor might study the elegant properties of a specific set of differential equations. An applied mathematician at Bosch takes those very equations and asks, “How can this help us build a better anti-lock braking system (ABS)?” The equations might be the perfect tool for modeling the dynamic friction between a tire and a wet road, the response time of a hydraulic valve, or the processing of a wheel-speed sensor signal. Academia might study the elegant properties of a specific set of differential equations and develop suitable solution methods; in the industrial setting, we build on those solutions to adapt them to our needs and extend them, for example, to complex geometries, feasible computational time, or strict memory requirements to name a few.

In a company as diverse as Bosch, the partnership between engineering and mathematics is fundamental. Engineering is the art of applying scientific principles to create solutions, and applied mathematics provides the essential foundation. It is the grammar of physics behind our sensors, the logic of control systems in our cars and factories, and the blueprint for efficiency in our home appliances. Without it, developing groundbreaking technology would be a slow, expensive process of trial and error, falling short of the precision and quality Bosch is known for.

The trinity of applied math in Bosch engineering

To understand the impact of applied mathematics across Bosch’s business sectors, let’s look at three core activities that are integral to our research and development process: modeling, simulation, and optimization.

1. Modeling: creating a digital blueprint of reality

The first step in tackling any complex engineering challenge is to translate it into the language of mathematics. This is called mathematical modeling. An engineer creates a model — a set of equations and logical rules that represent the system's key physical characteristics. Differential equations are the workhorses of this process. They describe how quantities change over time and space, which allows us to predict the behavior of technological components and systems to assess safety, performance and reliability early in the development process.

A key example is the Electronic Stability Program (ESP): When a car begins to skid, the ESP must intervene in milliseconds. This is only possible because of an underlying mathematical model of the vehicle's dynamics. This model, composed of complex differential equations, processes data from yaw-rate and wheel-speed sensors to understand the car's intended path versus its actual movement. It then calculates the precise braking force needed on individual wheels to bring the vehicle back under control. This is mathematics acting as a life-saving co-pilot.

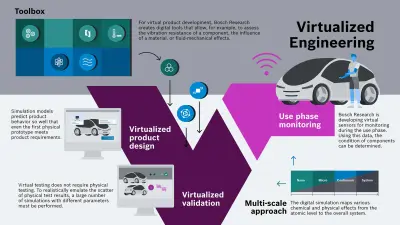

2. Simulation: the virtual proving ground

Once a mathematical model exists, its equations must be solved. For nearly all real-world Bosch products, these equations are far too complex for pen-and-paper solutions. This is where numerical simulation comes in: Using techniques like, for example, the Finite Element Method (FEM) or time integration schemes, those equations are broken down to smaller sub-problems which can be solved on modern computational hardware. Typically, this can take some seconds up to many days of computing time. Consequently, a lot of research is devoted to the question: “How can we speed-up those simulations?” There is no general answer, so we explore and adapt many promising approaches and solutions might differ depending on the product under investigation. Learning from data is key here. By combining physics with artificial intelligence, we are able to speed-up our simulations by many orders, which allows our engineers to test designs under thousands of conditions — like arctic cold or desert heat — without building a single physical prototype.

For example, before a new Bosch drill hits the market, it has already endured a lifetime of stress-testing in the digital world. Using FEM simulations, engineers can model the stresses and vibrations the tool will experience during heavy use. They can simulate it being dropped from a height, identify potential weak points in the design, and reinforce them, all within the computer. This digital testing ensures that the final product is robust, reliable, and meets the high standards professional customers expect.

Smartphones also rely on simulation. They use micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) — microscopic sensors that Bosch produces by the billion. An accelerometer, for example, measures motion by detecting the displacement of a tiny, suspended mass that moves when the phone accelerates. The behavior of this sub-millimeter structure is governed by a precise mathematical model of its mechanical and electrical properties. Simulation based on this model is essential for designing a sensor that can reliably distinguish between a gentle tilt, a sudden drop, or subtle vibrations, enabling features like screen orientation and fitness tracking.

3. Optimization: engineering the best possible solution

It is rarely enough to find a working solution; Bosch engineers are driven to find the best solution. This is the field of optimization: Given a set of constraints and targets (such as minimizing cost, weight, or energy consumption), optimization algorithms search for the design or strategy that finds the optimal solution satisfying the target but staying within the constraints. This typically requires thousands of simulation runs, again stressing the importance of speeding up simulation to make optimization procedures feasible.

Bosch’s eBike drive systems, for example, are renowned for their smooth and efficient power delivery. Engineers use mathematical algorithms to fine-tune the motor control software. The goal is to deliver power that feels natural and intuitive to the rider, while simultaneously maximizing the battery's range. The system must seamlessly blend the rider's pedaling effort with the motor's assistance, a complex balancing act perfected through mathematical optimization.

In a modern Bosch factory, autonomous mobile robots transport materials from the warehouse to the assembly line. The routes these robots take are not random; they are calculated by sophisticated optimization algorithms. These algorithms solve a massive logistics puzzle in real-time, determining the most efficient paths to avoid congestion, minimize travel time, and ensure the production line never waits for a part. This is optimization in action, making our manufacturing leaner, faster, and more competitive.

The future is forged in equations

The role of applied mathematics at Bosch is constantly evolving to meet the challenges of tomorrow. A key example is artificial intelligence (AI). At its core, AI is built on applied mathematics. Techniques like algebra, calculus, and probability theory are the foundations of the machine learning algorithms Bosch is developing for everything from automated driving to predictive maintenance.

A fascinating application is the creation of “surrogate models” to accelerate complex simulations, as mentioned before. A high-fidelity physics simulation — for example, modeling the fluid dynamics and electro-chemistry inside a fuel cell — can take hours or even days to run. To speed this up, a machine learning algorithm is trained on data from a few hundred of these detailed simulations to learn the complex relationship between the inputs (such as pressure and temperature) and the outputs (like efficiency or degradation). This creates a surrogate model that can predict the outcome of a simulation almost instantly. It allows our engineers to explore thousands of design variations in the time it would have taken to run just a few full simulations, dramatically accelerating innovation.

The ultimate expression of the modeling-simulation-optimization trinity is the “digital twin”: a living virtual replica of a physical product or production line. A digital twin of a manufacturing cell, for instance, is continuously fed with real-world data from its physical counterpart. Using this data, mathematical models can simulate future states, predict when a machine will need maintenance long before it fails, and test new process optimizations in the virtual world before deploying them in reality.

Looking further ahead, the next frontier lies in designing entirely new materials, and applied mathematics is key. For example, developing more efficient batteries, next-generation semiconductors, or powerful new magnets for electric motors requires understanding and predicting behavior at the atomistic level. The rise of quantum computing promises a new paradigm for solving these problems: Quantum computers are inherently suited to solving these quantum-level mathematical problems. By pioneering research in this area, Bosch is preparing to leverage quantum algorithms to simulate molecules and design novel materials with unprecedented speed and accuracy, opening doors to technological breakthroughs that are currently beyond our reach.

From theory to practice: cultivating mathematical excellence at Bosch

The powerful applications we create are never born by chance. They grow from a culture of continuous learning, open collaboration, and a profound respect for foundational science. At Bosch, we are deeply committed to nurturing a vibrant community of experts who turn mathematical ideas into real-world impact and transform theory into innovation that matters.

A perfect example of this commitment was our recent “Symposium of Applied Mathematics.” This event brought together our internal research and development community with leading minds from academia. We had the privilege of hosting four distinguished professors as keynote speakers, who shared their latest breakthroughs and inspired our own work. Alongside these keynotes, our own Bosch experts presented their successes and challenges in applying advanced mathematical methods to a broad range of products.

However, the true magic of such a symposium happens in the conversations between the talks. It’s where experts from one division discuss optimization challenges with experts from another, possibly sparking new ideas. It's where a PhD student can debate a complex modeling technique with a world-renowned academic. By creating these forums for exchange, we not only strengthen our ties with the global scientific community but also accelerate the scaling of powerful mathematical methods across all Bosch domains. It's this living, breathing network of people that truly powers the hidden engine of innovation, ensuring that mathematics will continue to help us create technology that is “Invented for life.”

What are your thoughts on this topic?

Please feel free to share them or to contact us directly.

Author 1

Michael Schick

Michael Schick is leading the research group “Applied Mathematics” and is a senior expert in the field “uncertainty quantification” at Bosch Research. His research focus lies on virtual validation: a combination of mathematics and artificial intelligence to boost the predictive capability of simulation models in engineering applications. Since Michael joined Bosch in 2015, he has worked with many different divisions, ranging from classical component simulation up to cyber-physical systems.

Michael holds a diploma in “Technical Mathematics” from the University of Karlsruhe (now KIT), where he also holds a PhD in applied mathematics.

Author 2

Uwe Iben

Uwe Iben is Chief Expert for Applied Mathematics at Bosch Research and an Honorary Professor at the University of Stuttgart. He is an expert in applied mathematics with a strong focus on the mathematical modeling of complex physical and engineering systems. His work combines classical methods such as partial differential equations, numerical analysis, and optimization with modern machine learning techniques. A particular emphasis is placed on TorchPhysics, an OpenSource and PyTorch-based framework for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), which he uses to efficiently solve physics-driven problems. Through this approach, Uwe bridges traditional mathematical modeling and data-driven AI, enabling innovative and industrially relevant simulation solutions.

Uwe holds both a diploma and a PhD in “Numerical Mathematics” from the University of Dresden. He also holds a PhD in “Process Engineering” from the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg.