Crises throughout the company’s history

“However, we have to power through at Bosch …”

World wars, turmoil in the financial markets, obsolete manufacturing methods, strategic impasses: there has always been one crisis or another throughout the history of Bosch. Each of them has been unique — some major that threaten its existence, others small but still stressful. The crises have usually been triggered or caused by an external event. They have tended to leave the company restricted in what it could and could not do. But problems of the company’s own making have also got it into difficulties. Bosch has always used crises as an opportunity to make lasting improvements. Focus and innovation have often been the result. Constant change, whether social or technological, has ensured the company’s continued survival.

Teething problems

“A shambles ...”

Robert Bosch on his safety bike, 1890

Only a few years after the company was established, Bosch experienced an existential crisis in 1892. It was triggered by payment difficulties on the part of a key customer coupled with a lack of reserves at Bosch. As is often the case with today’s start-ups, Bosch had focused on new technologies and wanted to develop electrical services and products. But the basic prerequisite was not yet in place: Stuttgart’s municipal authorities were not in a position to build an electric power station. This dry spell was longer than expected, and the market was unable to develop, with consequences for the new company. The number of associates fell from 24 to just two. On the brink of bankruptcy, Robert Bosch had to borrow money from his mother and take out a loan for which his family acted as guarantor. His perseverance paid off, however, and in 1893 the decision was finally made to build the power station. It went into operation two years later and brought with it sizable installation contracts.

“How I suffered during that time …” — Bosch strike

It was to be roughly another 20 years before the next crisis shook the company. It was triggered by a strike. It all started when eight workers, including a representative of the Association of German Metal Workers (Deutscher Metallarbeiter-Verband, or DMV), were dismissed in March 1913. The layoffs had become necessary following a drop in orders. An unannounced strike followed, whereupon Bosch threatened further dismissals. This turned out to be the beginning of a protracted escalation between company management on the one side and the unions on the other. The DMV called for a sit-down strike, demanding that everyone stop working. In response, Robert Bosch terminated all agreements. Another strike ensued, and Robert Bosch responded with a lock-out at the start of June. As someone who saw himself as a socially-minded businessman, Bosch felt misunderstood and suffered greatly from the conflict. Contrary to expectations, the lock-out of associates lasted almost two months.

Moreover, the working environment had become toxic. “The only thing worse was the rift that split the workforce because we had forced some people to break the strike,” Bosch wrote in his memoirs. “This rift was only resolved during the disastrous war, one year later. The outbreak of the strike at my plant was a great triumph for all those entrepreneurs who had been hostile to me ….” As a consequence, “Bosch the Red,” as he was referred to by other business owners at the time, joined the metal industry employers’ association feeling somewhat deflated. The move marked a change in his collaboration strategy: the union now had to negotiate with the employers’ association and could no longer approach him directly. However, the actual cause of the conflict was a major internal transformation.

Since the turn of the century, the small craft business had developed into an up-and-coming manufacturing enterprise. Sales increased exponentially, as did the number of associates. Loyalty to the company fell as the number of new associates rose, since there were fewer and fewer long-standing Bosch workforce members and Robert Bosch was no longer personally acquainted with all of his 4,500 associates. Structures were slow to change, and a middle management level was introduced, which made this personal contact possible again. The new manufacturing methods, such as Taylorism, were very unpopular with the workers. They had to work faster for the same wage, and many felt they were being subjected to undue pressure. However, the company had to keep up with progress in manufacturing if it wanted to remain competitive.

“… but without sacrificing our reputation” — quality not quantity

In the 1920s, the company found itself in its next crisis, caused by the consequences of the war and inflation, as well as internal structural issues. Before the war, the company generated 92 percent of its sales outside of Germany, roughly 25 million reichsmarks. That market disappeared completely. In addition, foreign assets were confiscated, and land, buildings, patents, and trademarks were lost. “Our market used to be the entire world, and we can only survive in our current size if our products are accepted in the world market again,” the company wrote in the annual report for 1919. Efforts were made to return to the levels of the prewar period.

The actual trigger was a crisis in the automotive industry in the mid-1920s: Ford and GM were offering low-price smaller cars that were produced in large numbers, while German manufacturers had missed the small car trend and were still using outdated manufacturing methods. Automakers passed on the price pressure to suppliers. This, coupled with structural problems and a lack of innovation, meant that Bosch had no choice but to take action.

First, Robert Bosch himself took charge of the future-oriented project aimed at developing a diesel injection pump, which went into production at the end of 1927. He also launched a systematic innovation plan. Next, the assembly line was introduced in 1925, which made production faster. However, the changes that followed, which Robert Bosch described in Bosch-Zünder in 1926, had a fundamental impact on the way Bosch associates saw themselves: “After lengthy deliberations, we have decided to meet the demands of our customers, who want to build very cheap cars, to the greatest extent possible without compromising the performance of our products. However, we have to power through at Bosch and make every effort to maintain the market, namely by using cheaper designs and the most economical products, but without sacrificing our reputation ….”

Other measures to secure the company’s long-term future included taking out loans. In addition, the board of management was restructured and given a stronger business focus, instead of a technical one. The expansion of the company’s foreign presence was supposed to broaden its position. At the same time, there were wide-scale dismissals: between September 1925 and September 1926, some 5,600 associates were laid off — nearly half the workforce. The Bosch community and its workforce’s sense of being were profoundly shaken: job security was a thing of the past.

It was not until late 1928 that Bosch was able to write to his Swedish representative, Fritz Egnell: “We now have our feet on solid ground again ....” In retrospect, the then chairman classified the years between 1924 and 1928 as the second creative period in the company’s history, in which “progress, price reduction, and expansion of the areas of application” formed the basic framework. This grounding was necessary because the global economic crisis in 1929 had an unusually strong impact on the automotive industry. In 1932, passenger car production fell to 40 percent of the level in 1928. In the mid-1930s, domestic sales at Bosch fell by 25 percent and foreign sales by 15 percent. Once again, associates were laid off, salaries were cut, and reduced working hours were introduced to keep as many workers as possible at the company. After the first wave, the company also diversified further through a series of acquisitions and by expanding production into new areas in order to give the company a broader base and therefore make it better able to cope with crises. The merger with Eisemann AG in 1926 resulted in the power tools division. In 1929, Bosch and partners set up Fernseh AG. The acquisition of the Junkers gas-fired appliance business in 1932 rounded out the product portfolio, and the first Bosch refrigerator was produced in 1933, with film and camera technology following one year later. A long-planned competition for ideas for new business opportunities was also launched.

“ … nearly insurmountable obstacles” — The second world war and its impact

In terms of productivity, the start of the second world war did not affect the company. Bosch was important to the war effort, and armaments production almost made up for the lost foreign sales. For the people at Bosch, the world war was a crisis of existence: men were called up for military service, and at least 1,365 of them died in the war. At the same time, the National Socialists terrorized the populace and the forced laborers who had been deported from their homelands, deployed in Germany in industry and other areas, and often forced to live and work in inhumane conditions. The company finally collapsed toward the end of the war, after many plants had been destroyed. Following the German surrender, the company had to stop production, and almost all associates lost their jobs. Moreover, all foreign assets were seized and foreign markets remained closed to the company for the foreseeable future.

As a result of the National Socialist era, Bosch had to overcome many turbulences in terms of people and the business. The annual report of 1946 had this to say: “We would have succumbed in the face of the nearly insurmountable obstacles had not the vast majority of our associates, filled with the spirit of our joint effort, supported us in such an exemplary manner right from the very outset. Whether it was debris removal, relocation of our departments and workshops, the reconstruction of destroyed production and administrative documents, or destroyed facilities ….”

“After years of uninterrupted economic growth …” — the end of the “economic miracle”

As early as 1948/49, however, the currency reform brought about an unexpected period of economic growth in West Germany. A period of unequivocal economic growth began in western Europe. Known as the “economic miracle,” the boom was to last almost 20 years.

This period came to an end with the economic downturn of 1966. Instead of a long, unchecked upswing, there followed a period of rapid cyclical shifts and volatile economic cycles — a development that even business leaders had to learn to deal with. The first countermeasures went down in Bosch history as the “October revolution”: investment and construction projects were halted, overheads were reduced, recruitment was stopped, overtime was banned, and the commission of higher wage groups was cut by 10 percent. The aim of the company was to avoid lay-offs.

In the years that followed, the board of management put even more emphasis into implementing the proven crisis strategies of internationalizing, diversifying, and expanding the company. It also adapted the company structure to its size: between 1946 and 1967, the number of associates multiplied from approximately 9,500 to some 84,000. Greater decentralization and freedom for the divisions was necessary to make sure they were more customer-oriented and competitive. A network of independently acting divisions was created. In purely legal terms, they continued to be part of Robert Bosch GmbH.

In its annual report for 1967, Bosch reported satisfactory business performance — the crisis had been overcome.

The first oil crisis in 1973, and the second oil crisis in 1979/80, caused renewed slumps in sales due to economic recessions. During this period, Bosch reacted with the “safe, clean, economical” campaign and its first own environmental protection guidelines, issued on January 15, 1973, which set out environmental issues.

“More than the organization can bear …” — the 1993 crisis

Some of the causes of the 1992/93 crisis were internal. During the boom of the previous years, which was primarily a result of exceptionally brisk economic activity following German reunification, Bosch had not done enough to reduce costs, since it was always able to push through price increases in the market. Marcus Bierich had already warned in 1987 of “serious structural shifts in the global automotive industry.” The massive expansion of Japanese and Korean automakers in the world market coincided with the peak of the business cycle in the automotive sector. Its massive slump in Europe in the second half of 1992 sparked fierce price competition, in which Bosch was at a disadvantage against many competitors and lost orders. Tough measures were implemented to compensate for the slump in business, as there were fears of an operating loss for the first time in the company’s postwar history. These included reduced working hours for 20,000 associates in Germany, as well as early retirement arrangements and termination agreements for some 13,000 people.

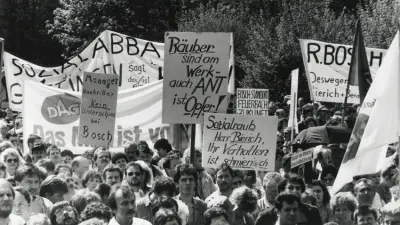

The result was an unprecedented demonstration by 11,000 associates outside corporate headquarters on April 26, 1993. “It was actually unimaginable for Bosch that something like this would ever happen,” former chairman of the board of management and supervisiory board Franz Fehrenbach recalls. “… Not enough attention had been paid to the extent to which the decisions made at that time affected the income of individual associates. For a simple wage earner, the income cuts were considerable, …and it took a very, very long time until a reasonable working relationship had been restored with the employee representatives.” The turmoil resulted in Marcus Bierich resigning as chairman of the board of management and Hermann Scholl taking over. In addition, the director of industrial relations, Günter Bensinger, was replaced by Tilman Todenhöfer, reducing the number of board of management members by four to a total of ten.

The tough measures bore fruit, but at the price of a damaged relationship of trust between the board of management and the workforce.

“Truly recognized the value of communication for the first time” — the financial and economic crisis of 2008/09

The next crisis with profound consequences for the company came some 15 years later, caused by the real estate and financial crisis in the U.S. The annual report states: “The 2008 business year … ended with sharp declines across all units …. Worldwide, the economy went into reverse at a speed and on a scale that were practically unprecedented. … For our associates, this also brings hardships. Insofar as possible, however, our priority remains to cushion fluctuations in employment through flexible organization of working time ….”

The measures consisted of a two-week shutdown at the plants at the turn of the year 2008/09 and a reduction of overtime accounts and weekly working hours to 31.5. When this was not enough, a shorter working week was introduced (at the end of April 1993, there were 93,000 associates, 58,000 in Germany). Executives and members of the board of management did not receive a salary increase for two years, and their bonus was cut. What was crucial was that the company had learned from what happened in 1992/93 with regard to communication between executives and associates, Franz Fehrenbach recalls: “Then we communicated much more …. We started having conference calls, which did not exist before .... We increased the [number of] associate letters ..., we became much more open and also truly recognized the value of communication for the first time.”

Alongside innovative products, acquisitions such as Rexroth and Buderus also contributed to the recovery. The strategic orientation proved to be the right one, and the increase in the share of international sales from 49 percent (1993) to 75 percent (2008) also brought advantages. At the same time, progress was made in areas of future significance with regard to greater energy efficiency, resource conservation, and environmental protection.

It was therefore not a structural crisis that made restructuring necessary. The turning point came earlier than expected in September 2009. By the end of the year, however, 28,500 associates still had a shorter working week, 27,000 additional associates were working shorter hours, and there were 10,000 fewer jobs abroad than in the previous year.

Using well proven strengths to overcome a difficult time

The company entered a new dimension of crisis in 2020. An unprecedented combination of structural problems, which became apparent as early as 2019, and the existentially life-threatening coronavirus pandemic hit at the same time. In April 2020, the board of management started to implement measures to secure liquidity, such as taking out loans and introducing a shorter working week, which was partially converted into reduced working hours in August.

Looking back at the various crises over the history of the company, it is clear that the strategies for overcoming them have been the same even though the triggers and causes have varied. Important factors such as internationalization, expanding the business fields, broadening the product range, and innovative manufacturing methods were the key to overcoming the crises. The principles behind this are willingness to change in a changing world and orientation to the Bosch values.