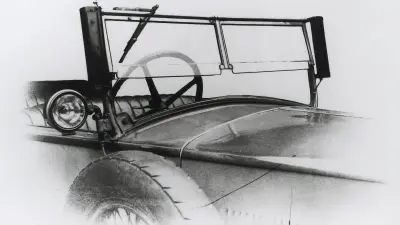

Bosch ignition for motor vehicles

Bosch‘s mechanic Zähringer found a solution

Back in 1897, the Bosch magneto ignition device was a high-tech product, unlike any before it — game-changing and suited for mass production. It was a breakthrough that finally gave carmakers ignition systems that would make the automobile an everyday mode of transportation. The new product paved the way for Robert Bosch’s small courtyard-entrance workshop to become a global company.

Who would have thought that, within the space of a single decade, one innovation would make Bosch the leading provider of automotive ignition systems on all continents? The idea was simply ingenious: to use an everyday product somewhere else, somewhere it was urgently needed — in automobiles. The Bosch magneto ignition system helped the then new technology of motor vehicles overcome a crucial obstacle to its success by improving the reliability of the process used to ignite fuel in engines. Back in 1897, Bosch probably could not have anticipated the success that the magneto would one day enjoy. Let us start from the beginning.

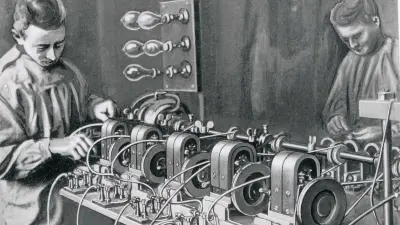

Until the mid-1890s, Bosch had to live with an uncertain financial situation – with the ups and downs of a precision mechanic making repairs and installing machinery, like so many other small businesses in Stuttgart. Stability and modest growth did not arrive until the advent of a reliable power supply. In 1895, Stuttgart’s first electricity works enabled Bosch to start offering his services in the field of electrical engineering. After all, installing electric lighting was not a job that just anyone could have done back then. With a stable staff of just under 20 associates, the entire Bosch team still fit around a large restaurant table during its company outing in 1896.

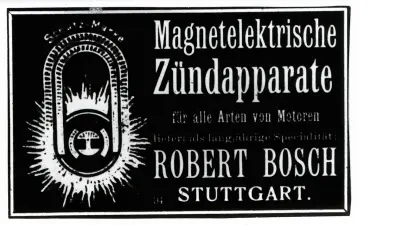

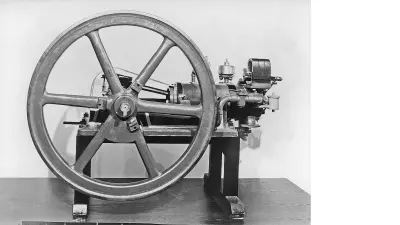

But success was just around the corner. Around 1895, automotive pioneers started misusing a popular product from Bosch’s workshop for their motor vehicles: the magneto ignition device. Such magneto-electrical ignition devices had existed since the 1860s and were used frequently in stationary engines. While Bosch did not invent the technology, the company started offering magneto ignition devices in 1887. Associates would manufacture the individual pieces by hand over a period of weeks. The ignition devices were designed for large, low-speed stationary engines. For Bosch, they were a mainstay, accounting for up to 50 percent of his small workshop’s sales as the 1890s began.

Because motor vehicles featured much smaller engines that had to operate at a far higher speed in order to provide the necessary output, ignition proved to be the “trickiest problem,” as one automotive pioneer put it.

The moment that changed everything came in 1897, when a customer asked Bosch to customize a three-wheeler with a magneto ignition system. Robert Bosch tasked his factory manager, Arnold Zähringer, with finding a solution, which he delivered by making a fundamental design modification.

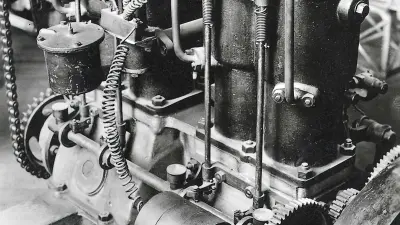

The decisive breakthrough? Until then, the electrical energy had been generated through the rotation or oscillation of an armature wound in copper within a magnetic field. The technology was capable of providing ignition at 100 rpm, but was insufficient in smaller, faster vehicle motors that operated at up to 1,000 rpm. Zähringer set it up so that a lightweight metallic sleeve surrounding the armature would rotate or oscillate instead, enabling a large number of ignition processes.

Bosch filed the first patent in the company’s history on June 11, 1897. Word of the new technology spread like wildfire. After producing some 1,000 ignition devices for stationary engines in the ten years between 1887 and 1897, annual production volume increased exponentially over the five years that followed. By 1912, that number stood at 1 million in total. Suddenly, Robert Bosch no longer had to worry about keeping his staff occupied.

The magneto ignition

How does it work?

Until Robert Bosch got involved, there were two competing systems: glow-tube ignition, which required an extremely dangerous open flame, and battery-powered ignition, which provided electrical energy for ignition sparks until the battery ran out of power. The disadvantage of the latter was its limited range.

Bosch’s automotive ignition system was powered by the motion of the engine’s crankshaft, eliminating its dependence on a battery. The concept made use of the rotation or oscillation of a metallic sleeve surrounding a double-T armature wrapped in copper in a magnetic field. The mechanically controlled interruption of the power circuit at a contact point in the engine compartment at the moment of the maximum charge reliably and rapidly generated the spark that ignited the air-fuel mix and kept the vehicle safely in motion.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz