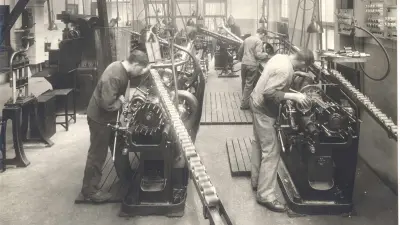

When assembly-line production began at Bosch

“Out of the crates, down from the carts!”

Economic challenges in turbulent times call for new approaches. One hundred years ago, Bosch modernized its manufacturing operations, and the resulting efficiency gains helped the company reclaim its competitiveness. The process took a number of steps.

Relocating machinery

It was a hive of activity. After 1923, the Bosch plant in Stuttgart was even louder than usual, following the introduction of a new manufacturing system. Known as group manufacturing, it was designed to make production more economical. Since it required work processes to be assigned to individual groups and placed physically near each other, the change involved a lot of physical reorganization. Each individual workshop had to have the required machinery and tools on hand, so that the complete product could be manufactured in a multistep process. To simplify production processes and shorten transport routes, materials were gradually moved to new locations in the plant.

The age of the workshop

Before that time, Bosch had largely organized its manufacturing in workshops. Each individual workshop did its own turning, milling, grinding, and drilling work, regardless of the overall product. Depending on the complexity of the process, work was sometimes completed more quickly in one workshop than in another. Semi-finished parts were first sent to a large warehouse, from where another workshop would retrieve them for use in a further work step. So it continued until the finished product was finally ready. A lot of storage capacity was needed, and transport routes were long. In addition, there were often long idle times during the manufacture of a product. For smaller batch sizes, however, it was also possible to take individual customer wishes into account.

Competition gets tougher

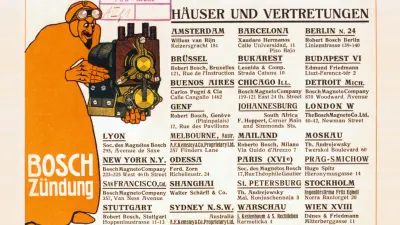

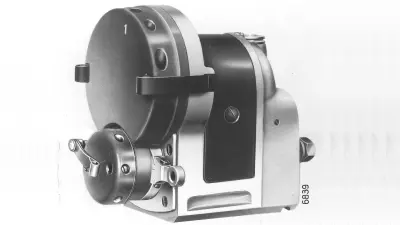

In the economically prosperous times before the first world war, when Bosch was one of the few manufacturers to sell its high-quality magneto ignition devices all over the world, time and specialization were negligible factors. Later, during the four years of wartime production, manufacturing operations had to produce quickly and in large volumes. There was no time for scientific production planning. When the war ended, the situation was very different. Worldwide, other strong competitors were now manufacturing magneto ignition devices, offering products of a similar quality – often at a lower price. Bosch management had no choice but to review its production processes and find ways of making them more efficient and economical.

Scientific management and assembly lines

Other companies had already taken steps in this direction. Starting at the end of the 19th century, the theory of scientific management took hold at manufacturing companies across the United States. It was first formulated by Frederick Winslow Taylor, who analyzed and combined work processes to make them more efficient. In addition to optimizing human effort, machine efficiency was key to Taylor’s ideas. Scientific management also resulted in the introduction of more and more assembly-line work in large factories. One pioneer in this field was Henry Ford, who had been producing cars on assembly lines in his factories since 1913. In Europe, this development was delayed until after the first world war.

It all starts with standardization

Bosch also realized that scientific management offered it a way of withstanding tough economic conditions. Besides new products and new sales markets, the rationalization of production offered a third way of putting the company on a robust footing. As an automotive supplier, however, Bosch could not simply copy Ford’s concept. While Ford’s Model T cars were similar down to the last detail, this was not the case for products made by Bosch. In the mid-1920s, there were 44 basic types of magneto ignition device. On top of that, there were subtle differences between these individual devices’ components. The adjustment lever needed for optimum ignition timing was a good example. Bosch initially reduced the number of types of this part from 700 to 400. A variance of 30 would have been sufficient, but customers demanded more. This made it difficult to create the conditions for more efficient manufacturing.

The horn as a test case

For assembly-line production, therefore, the first step was to identify products that could manage with a small number of types. The recently launched Bosch horn presented a perfect opportunity. Within a few years, its manufacture was converted to assembly-line production, and the time to produce a complete horn was reduced from 14 to 4 days. The company also managed to save 25 percent on labor costs and 60 percent on storage costs.

Smooth-flowing production

Bosch also relied on smooth workflows when making its magneto ignition devices. For the turning and milling of the housings, the blanks traveled via a sloping conveyor belt to the worker, who processed them and placed them on the neighboring sloping conveyor belt for delivery to the workers further down the line. The process continued smoothly, unhindered by transport crates and the need to deliver parts on carts. Once a workshop had created a finished product, it was generally ready for immediate shipment.

This combination of group manufacturing and assembly lines allowed Bosch to reduce the production time for a magneto ignition device from 50 days to 4. As a result, the company could offer it at a lower price.

Manufacturing expertise

Rationalizing production in this way helped Bosch to cushion the effects of economic turbulence in the 1920s and to regain a leading position in the face of tough competition. Ever since the company was founded in 1886, a high level of manufacturing expertise has been a key success factor for Bosch. And this story has continued via the first industrial robots to today’s smart factories.

Author: Christine Siegel