The transformation of Bosch’s legal form over the years

A capital idea

Today’s Bosch is a company with more than 420,000 associates worldwide. Most other businesses this size are stock corporations. Bosch is not — or at least not anymore. Between 1917 and 1937, though, Bosch was a stock corporation known as Robert Bosch A.G. Since then, the company has been a close corporation. What led to these decisions?

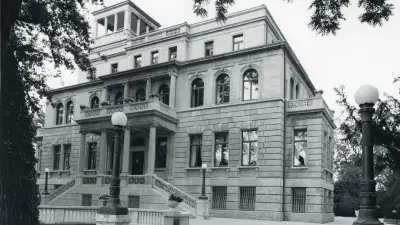

The mood around the dinner table at the Bosch family home in May 1913 must have been highly charged. A strike was in progress at the company’s plants. The developments came as a shock to Robert Bosch, who had always paid fair wages and strived for consensus with his associates. However, his 25- and 23-year-old daughters, Margarete and Paula, had chosen to side with the striking workers, in opposition to their father. Exasperated, Robert Bosch wrote to his wife, Anna, who had taken their ailing son out of town for treatment: “I at least shouldn’t have to expect to be attacked at home as well.”

Gaining a stake in the company’s success

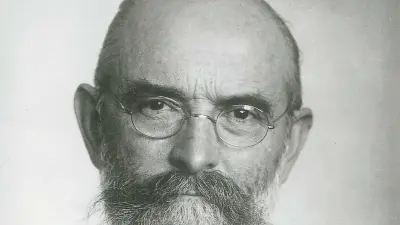

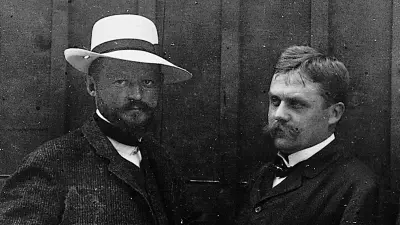

The circumstances within the family — the incurably ill son Robert, who would not be able to take over the business, and the daughters who stood in opposition to their father — were met with apprehension by the company’s senior executives. Gustav Klein, Bosch’s director of international sales, and Gottlob Honold, the head of research and development, led the charge of calling for a new company form that would allow them to take a stake in the success of the business they were helping to build. Robert Bosch was open to their demands, in keeping with his style of leadership. What is more, the company would never have grown as quickly and successfully without his inner circle of close associates. Honold’s advancement of the magneto ignition and Klein’s tireless efforts to set up and support Bosch companies outside of Germany had helped the business gain an incredible amount of momentum. Those involved were interested in protecting such achievements from potential harm should the founder’s heirs one day take the reins.

“The guiding thought was: the company must be insured against improper interjections and interference by my heirs.”

Looking for the form

Klein proposed to Robert Bosch that he set up an ordinary partnership, or offene Handelsgesellschaft, and give the company’s senior executives a stake in the business. Paul Scheuing, Bosch’s legal adviser, voiced his support for a joint stock corporation, or Kapitalgesellschaft. That would have given the senior executives an opportunity to acquire a stake in the company by making a capital contribution, turning them into shareholders. As a result, Robert Bosch’s children would only have been entitled to his personal shares in the company, rather than the whole business, in the event of his death. However, the outbreak of the first world war prevented a fast solution.

By 1917, the situation had changed. Klein had died in a plane crash, and Robert Bosch was suffering from cardiac dilation. The need to find a new company form was urgent. Scheuing once again proposed setting up a joint stock corporation. In fall 1917, Robert Bosch A.G. was founded. Robert Bosch merged the business he had run on his own up until that point into the newly established company. However, the shares were never put up for trading on the stock market. Instead, the senior executives Gottlob Honold, Ernst Ulmer, Eugen Kayser, Heinrich Kempter, Max Rall, and Hugo Borst acquired varying proportions of the company’s shares totaling 49 percent, with Robert Bosch keeping the other 51 percent. In the event of Bosch’s incapacity, the shareholders would be able to buy 2 percent of the shares, thereby acquiring a majority stake in the company. That way, the business would remain in familiar hands no matter what, allowing its managers to continue pursuing the same business policy as in the past.

Irony of fate

Although most of the board members and shareholders were relatively young men compared to Robert Bosch, Kayser, Kempter, Ulmer, and Honold died unexpectedly between 1918 and 1923. Robert Bosch was emotionally deeply affected not only by the personal loss of his long-standing contemporaries, but also by the fact that the shares were now in the hands of heirs from outside the company. Paradoxically, the new company form, which was intended to reduce the influence of Bosch’s heirs on the business, now appeared poised to help other heirs gain an unexpected position of power. As a result, he gradually bought back nearly all of the shares during the 1920s and 30s.

Conversion to a close corporation

An amendment to German corporate law in 1937 triggered a series of changes. Among other things, it strengthened the position of the board of management in its dealings with the supervisory board. The changes were of great concern to the body’s chairman, Robert Bosch. However, the new law also made it easier to pass decisions despite the objections of minority shareholders. Robert Bosch took advantage of the new rules to change the company’s legal form that same year and transform the stock corporation into a close corporation, or Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung (GmbH). In doing so, Robert Bosch also hoped to preserve his influence as owner and chairman of the supervisory board for himself and his family. Having had another son in 1928, he amended his will in 1938 to stipulate a permanent connection between his family and the company.

In addition, he requested that parts of the company’s revenue be appropriated for charitable causes. Since 1964, the nonprofit Robert Bosch Stiftung has been seeing to that. Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH holds roughly 94 percent of the shares in Robert Bosch GmbH. Meanwhile, Robert Bosch Industrietreuhand KG holds 93 percent of the voting rights, allowing it to carry out the entrepreneurial ownership functions.

Author: Christine Siegel