Analog, digital, connected

A look back at Bosch automotive electronics

It began with a visionary idea: Bosch applied for its first patent for an electronics product — an ignition unit for engines that was controlled using electronic tubes — over 100 years ago. However, the idea never got off the ground, as shaking during use damaged the tubes. As so often, the first step was the hardest.

The success story did not start for Bosch until some 60 years ago, with semiconductor technology that made it possible to use electronics in cars. Their engineering and production was challenging, but these electronic helpers have made technology more reliable, powerful, and affordable. Without semiconductors and electronics, Bosch would not be the global player it is today. But the road to get there was a rocky one.

Why would a company get involved in a line of business that no one at the company really knows much about and in which no one has any practical experience? At Bosch, the reason to do so was actually quite simple: the hope was that semiconductor components, which were cutting-edge at the time, would make it possible to build new and appealing products while increasing the reliability of automotive technology and decreasing the need for maintenance or repairs.

Making cars better from the ground up was a tempting vision for the future. But because Bosch had to buy semiconductor components that were developed for consumer electronics, it faced the fundamental question of how to ensure the necessary reliability for the tough conditions in a vehicle. In a television, semiconductor technology does not have to withstand everything from Arctic cold to scorching heat — but under the hood of a car it does.

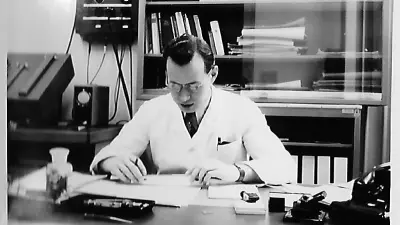

Faced with this reality, Bosch decided in the 1950s to start developing semiconductor elements for cars itself and to engineer them from the start to take on the challenging conditions found in motor vehicles. Bosch applied for its first semiconductor patent in 1958 — for a semiconductor diode used in an alternator regulator. As Bosch’s strengths had traditionally been the manufacturing of high-quality mechanical products, the patent application marked a major step in the company’s reinvention. Building up a broad base of expertise within the company, however, remained a challenge.

“Attracting the bright sparks away from the semiconductor companies was simply impossible. There was no literature, either. So we had to study patent specifications.”

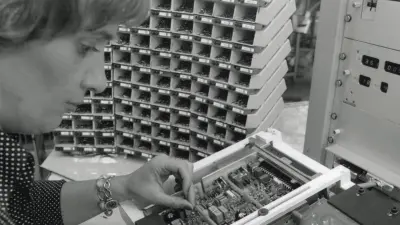

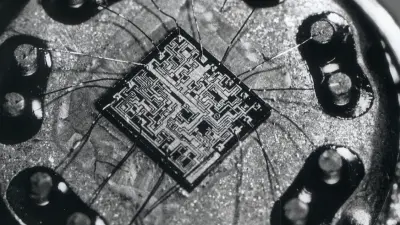

Yet expertise was what the company needed, especially for the development of application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) for cars starting in the mid-1960s. Because vehicle electronics are exposed to particularly demanding mechanical and climatic conditions, integrated circuits have a decisive advantage: they make it possible to combine hundreds of functions in a single component, significantly reducing the risk that individual functions might fail. To make sure it had access to sound semiconductor products, Bosch decided to set up its own production facilities rather than relying on suppliers.

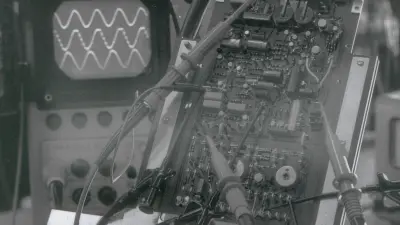

Electronics were uncharted territory for automotive industry customers, meaning that Bosch could not rely solely on suppliers to ensure quality. The launch of a new technology was at stake. The use of electronic components in alternators and ignition systems was followed by more sophisticated electronics such as gasoline injection, which involves gaining control over complex processes that meter the amount of fuel going to the engine depending on the current conditions so that it functions optimally while keeping emissions and fuel consumption low.

“The first electronic components definitely proved their worth, so it just made sense for Bosch to start working on electronic control units.”

The Jetronic electronic gasoline injection system was an important milestone on the road to success for automotive electronics. Launched in 1967, the technology bore the stamp of future Bosch CEO Hermann Scholl and made it possible to comply with strict emission standards, acting as a blueprint for future developments.

During this era, Bosch manufactured increasingly sophisticated electronics and built a manufacturing plant for semiconductor-based electronics in Reutlingen, establishing an in-house supplier in 1974 that would become today’s Automotive Electronics division.

Analog electronics, with hundreds of individual components in a control unit and the combination of multiple functions in integrated circuits, was followed by digital electronics, with programmable memory and microprocessors, in the 1970s. Around this time, a consensus started to emerge regarding the necessity of a wide range of electronic functions for cars as a central pillar of any future strategy. However, the traditional circuit board technology, with soldered components, proved to be a weakness. When expensive cars break down on the road, it puts automakers in a difficult situation and has the potential to damage the reputation of suppliers such as Bosch. Hybrid technology – which features functions that have been fired onto a ceramic substrate and provides far greater reliability and a longer service life despite using significantly more complex manufacturing technology – offered a solution to that problem.

“The customer wants quality, and quality simply means that it works and will always work.”

In 1979, Bosch began producing its first digital engine control system that controlled both ignition and fuel injection at the same time. Motronic, as it was known, marked a breakthrough in engine management. As the first automotive system that was necessary for driving, Motronic featured a freely programmable control unit. The software enabled flexibility and could be adapted to allow the use of the same control unit in a different model, ushering in the age of the computer in the automobile. Starting in the late 1970s, Bosch increasingly focused on developing systems aimed at preventing accidents or mitigating their consequences. The ABS antilock braking system from 1978 is an example of this undertaking, as is the Bosch airbag control unit, which entered production in 1980. The ESP electronic stability program was even able to keep a vehicle on course when drivers were about to lose control.

With airbags, ABS, and Motronic on board, the company had to start looking for ways to connect each electronic system with the next to ensure smooth interaction between the separate control units despite the miles of wiring found in a car. It also had to make sure their functions were coordinated and properly orchestrated.

In the 1980s, the company therefore started thinking about a standardized data protocol for information transmission in cars, leading to the launch of the controller area network (CAN) in 1991. The CAN enabled the fast and precise exchange of information between sensors, electronic control units, and actuators – such as valves or switches — while still allowing the entire system to prioritize the activation of essential safety functions such as ESP within milliseconds to prevent the car from skidding, for example.

“Suddenly we had to write software. You had a completely different freedom, different dimensions for design, which was already a huge step.”

Another element also plays a role in ensuring that electronics function optimally: sensors. First developed in the late 1980s, microelectromechanical sensors (MEMS), were a milestone in this field. Bosch used the innovative breakthrough in automotive technology. These tiny helpers, some just 1.5 millimeters in size and equipped with moving parts, paved the way for Bosch to become the market leader in automotive sensors. One major advantage is that MEMS can be manufactured using a procedure similar to electronic switches. Both products are applied a thousand times over to a large silicon wafer in a sophisticated photochemical process and then split up into the individual components, known as chips or microchips. For MEMS, Bosch developed an innovative plasma etching production process that makes it possible to precisely form the tiny movable structures. Known as the “Bosch process,” it has since become the global standard in microelectronics.

“Microelectronics need some type of sensory organs to be able to perceive the environment.”

Resting on the shoulders of the technical solutions developed at Bosch in the field of automotive electronics over the past 60 or so years are many future driving scenarios that would have been virtually unthinkable just a decade ago but are now reality in some cases. Among them are self-driving cars that can independently use the web to share data with other vehicles — all with the goal of preventing accidents, reducing traffic jams, and saving energy.

Even in the future, physical electronics will remain the technical basis for web-based mobility solutions, with connected control units, sensors, and actuators. They will also form the foundation for artificial intelligence, which makes it possible for electronic systems to learn and helps conserve resources and prevent accidents.

See and hear reports from time witnesses in developing electronics

Loading the video requires your consent. If you agree by clicking on the Play icon, the video will load and data will be transmitted to Google as well as information will be accessed and stored by Google on your device. Google may be able to link these data or information with existing data.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz