Rebuilding the first Bosch equipped automobile: A contemporary witness reports

Alfred Raiser, a thoroughbred technician, training manager, and process facilitator, had barely retired-and already he was accompanying the exciting changes in the digital Bosch world as a member of Bosch Management Support, an expert organization made up of former associates.

Back in 1997, you and a group of apprentices and trainers from the German Bosch locations in Schwieberdingen, Reutlingen, and Bühl presented a replica of the historic De Dion-Bouton three-wheeler to the board of management. What was the story behind the project?

It’s quite a long story. The corporate department for education and training wanted us to develop a new occupational training system in Schwieberdingen, where I was the head of training. To have a sound foundation for this task, I studied adult education and completed training in organizational development and coaching. The new system that we developed was rolled out in all training departments in Germany.

“Questions were answered with questions, thereby encouraging the apprentices to think things through.”

What was new about the system?

In occupational training, you have to develop not just expertise, but interpersonal skills as well. Shift supervisors now took a different approach to teaching their apprentices − questions were answered with questions, thereby encouraging the apprentices to think things through. We wanted our apprentices to find out if there was a system behind things. The shift supervisors worked closely with the vocational colleges, and while they were responsible for the theoretical subjects, we were responsible for practical training. There were frequent regular meetings to ensure everyone was pulling in the same direction. The apprentices took on more and more demanding tasks, and set up their own self-help groups in which the stronger participants supported the weaker ones.

When and why did you come up with the idea of replicating the three-wheeler?

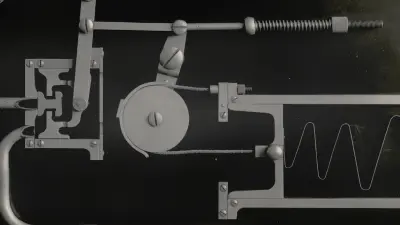

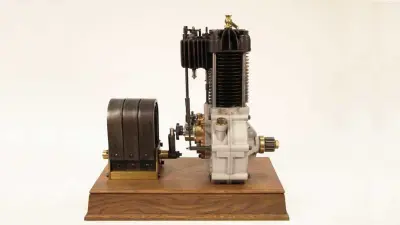

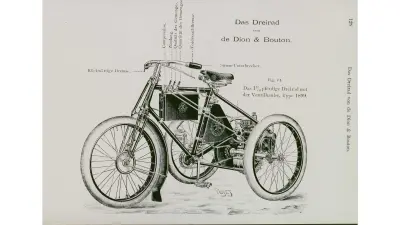

We thought it would be a good way of marking the 100th anniversary of the Bosch magneto ignition, especially considering that it was an apprentice of Robert Bosch who first tried out the magneto on a motorized three-wheeler. It also helped to bring the training departments at different locations together. Each was able to contribute its expertise. The idea was that the people from Reutlingen would build the frame and the wheels, the people from Schwieberdingen would be responsible for – what else? – the engine, and the people from Bühl, who are more electrically inclined, would make the ignition device.

“It got the apprentices excited and motivated, but it also challenged them.”

I take it you had the original plans for the De Dion-Bouton three-wheeler?

No, that was one of the main problems. We did some research and ultimately found one of the original three-wheelers in a small museum of technology in France. We went there with a few apprentices, took pictures of it, measured it, and drew a few sketches. The dimensions were just to give us a general idea of the whole thing, of course. We also managed to get our hands on a general technical description. And then we got to work. We had a small engine, and asked a technical college with a molding training program to help us cast it. For the most part, the apprentices reconstructed the component parts and the carburetor – a very demanding task. We got the pistons from Mahle; it pays to have friends sometimes. We tried to chase down other parts such as cylinder rings and valves as best we could. What’s more, we couldn’t just go to the gas station to get the fuel we needed. So the research department at a mineral oil company brought us a big canister of gasoline that was free of aromatic compounds. However, there were some things that we couldn’t replicate authentically. For example, we had to install heavy-duty magnets because magnetizable steel wasn’t available anymore. All in all, we learned an incredible amount in the course of the project. It got the apprentices excited and motivated, but it also challenged them.

The replica was presented to the board of management at Schillerhöhe. Did the three-wheeler function smoothly?

Not quite. It was quite a nail-biter. The board of management members and the chairman of the supervisory board had gathered expectantly outside the high-rise at Schillerhöhe. The three-wheeler was parked in a big conference room. We couldn’t leave it with the fuel tank full because of the risk of explosion. We ran outside, pushing the three-wheeler, all the while filling it up with gasoline in the hope that it would make its way down into the tank in time. You had to jump up on the three-wheeler as soon as the engine started, since there was no way of stopping it, so one of the apprentices hopped on while another turned the crank. The three-wheeler got off to a pretty stuttering start. We had hoped that everything would go smoothly, but our guests were very good about it. We were extremely relieved when Mr. Scholl, the chairman of the board of management at the time, told us it was a problem he had experienced himself in the early days of electronic gasoline injection.

Still, after two years and generations of apprentices working on it, our De Dion-Bouton three-wheeler was finally fully functional. And after making stops in Bosch sites in Schwieberdingen, Bühl, and Reutlingen, we handed over this one-of-a-kind vehicle to the Bosch Archives. After all, the low-voltage magneto ignition device for the De Dion-Bouton three-wheeler was the starting point of Robert Bosch’s career as an automotive supplier.

Author: Angelika Merkle