A history of Bosch technology for better living

From the light of a bulb to energy efficiency

What is a modern home? In an era of climate change, it is a place to live that saves energy and produces as little CO₂ as possible. More than a century ago, Bosch was already engineering technology that made modern living possible. In the early days of the company, modern living referred to the installation of electric lighting. Later, it meant the electrical refrigeration of food or the heating of rooms and water. For almost 50 years, saving energy has been a major focal point — something Bosch is helping people achieve through innovation.

Let there be light — installed by Robert Bosch

Without pioneers like Robert Bosch, living rooms would never have been bathed in the glow of electric light so soon. Despite having been trained in the traditional profession of precision mechanics, Bosch’s true passion, from the very start, was for breaking new ground. His desire to innovate led him to the forward-looking field of electrical engineering. However, Stuttgart was still far away from having its own generating plants and power infrastructure. In 1895, Stuttgart opened its first electricity works, supplying homes with electric light and bell pull systems. The number of people working at Bosch increased to 14, and sales revenue doubled within the space of a year from 39,000 to 80,000 marks.

Goodbye, ice and coal

A little more than 30 years after his workshop’s initial success, Robert Bosch’s groundbreaking ignition system had made him the world’s leading automotive supplier.

But a severe sales crisis in the automotive industry shifted his focus back to technology for life at home. In 1933, Bosch built the first electric refrigerator that was designed to be affordable for private households in Europe. As a result, people no longer had to buy a massive block of ice in winter and have it transported to their homes so that they could chip off pieces over the course of the year to keep food cool.

The days of having to carry coal through homes, from stove to stove, also soon came to an end. The acquisition of the Junkers division for gas-powered water heaters in 1932 made it possible to hook up water heaters and home heating appliances to the gas grid, with powerful and efficient gas-fired boilers now capable of centrally heating rooms or entire homes.

Energy from the sun and air

The focus of Bosch’s residential technology was always on comfort, technical advancement, and simplifying life at home. Those elements remain important to this day, along with other decisive factors such as the conservation of resources and sustainability. Efficiency already played an essential role in the heating technology of the 1930s, initially for financial reasons, but became an even more significant aspect following the 1973 oil crisis.

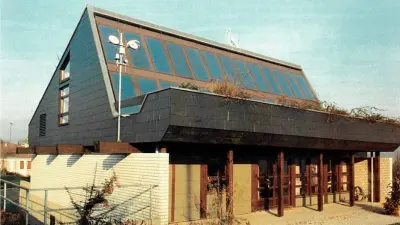

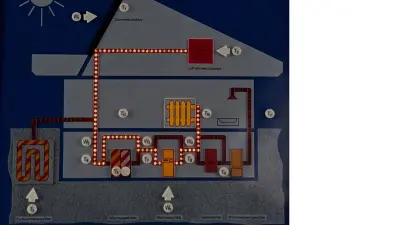

One special example is the experimental “Tritherm house.” Built in 1976 in the Stuttgart-area town of Wernau by the Bosch Thermotechnology division, the predecessor of today’s Bosch Home Comfort Group, it was engineered to showcase the feasibility of an energy-efficient home. Architects designed the house so that even large groups of visitors could tour the equipment and get a glimpse behind the scenes. There, Bosch experts would tell them about the efficiency-boosting technology, which used solar thermal systems and heat pumps to reduce fossil energy consumption by up to 90 percent compared to conventional houses. Such numbers were appealing in the years immediately following the first global oil crisis. Apart from drawing attention to the finite nature of fossil fuels and the resulting problems, the pioneering experimental house also underscored the commitment of Bosch’s researchers to explore new ways of combating the rise in environmental pollution by demonstrating the possibilities.

The heat pump: development, failure, and rebirth

While the experts from Bosch often succeeded in developing technical innovations and pushing the boundaries of what was feasible, manufacturing the complex technology at acceptable prices often proved impossible. Geothermal and air source heat pumps, which Bosch presented for the first time back in 1972, were unable to gain a foothold in the market in times of cheap fossil fuels. However, the principle remained convincing, and is now more relevant than ever. Heat pumps absorb heat from the ground or the surrounding air and are capable of producing far more energy to heat a home than they require, in the form of electricity, to operate.

Summary

Even though the heat pump did not succeed in conquering the market at first, researchers were able to set a technological course for the future of providing homes with energy that Bosch is now systematically pursuing. The extensive investments that were required are paying off as a strategy for greater energy efficiency. Today, heat pumps are an established technology for resource conservation and more climate action. Their operation makes the heating of a house almost CO₂-neutral, if the electricity they need comes from renewable sources like the sun, wind, or water.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz