Internationalization strategy after the first world war

Back to the global stage

Had Robert Bosch not been so quick to realize that Germany alone could not offer him a big enough market and that it was necessary to develop an internationalization strategy, it is unlikely his company would ever have been so successful. The sale of magneto ignition devices outside Germany was an essential pillar of Bosch’s success, and it prompted the company to start producing its best-known product abroad as well. Prior to the outbreak of the first world war in 1914, Bosch was generating almost 90 percent of its sales outside its home country — a figure that remains unmatched to this day.

With famed quality against the challenges of internationalization

Once the war was over, therefore, the company’s internationalization strategy turned once more to the global market. However, apart from continuing inflation, which favoured exports in Germany, the starting conditions for the process of internationalization were anything but favourable. In the years following the war’s end in November 1918, Bosch faced a variety of challenges in international markets. Patents and international subsidiaries had been unconditionally expropriated and sold in important automotive markets such as the United States, France and the United Kingdom. As a result, Bosch had lost its status as practically the only manufacturer of magneto ignition devices, and now found itself faced with a number of competitors.

Moreover, international sentiment was not particularly favorable to German companies, even though many customers around the world still held Bosch’s high-quality products in high esteem.

To remind customers of its products’ famed quality, Bosch started exhibiting its product range at international trade fairs. Back in 1920, motor shows were still small affairs. Usually the company would set up and decorate a single table, as it did in Prague and Zurich. The focus was not so much on showcasing the company’s portfolio as on re-establishing contact with an international clientele.

“From our foreign correspondence, we have learned that our products are remembered rather fondly everywhere and that we would probably be able to compete wherever quality is the deciding factor.”

Getting back in touch with international business partners

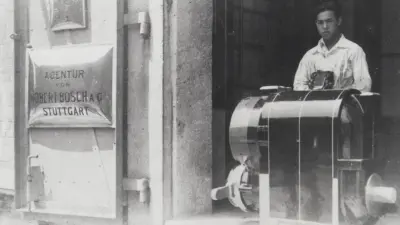

Rebuilding the international sales network was another difficult yet vital task for the company’s strategic management. Helped by the high rate of inflation in Germany, the export of products had become an important tool for taking the sting out of the postwar economic chaos. But where to start? One part of the company’s internationalization strategy was aimed at getting back in touch with old business contacts outside Germany and resuming international business operations that had previously taken place. In the countries that had remained neutral during the first world war, Bosch's senior management found the same old partners with whom they had worked before the conflict broke out. These former international business partners were more than happy to start selling Bosch products again — something they had stopped doing during the war due to a lack of supplies. In 1920, Bosch renewed its relationship with the Danish company Jebsen & Jessen, which had sold Bosch products in China before the war. That same year, the company Illies & Co. resumed its work as Bosch’s sales partner in Japan, also adding the Korean market to the mix. And in Switzerland, Bosch set up Robert Bosch S.A. Zürich/Genf, its first own company outside the domestic market after the first world war.

A new beginning in Great Britain and France

Rebuilding business relationships in the countries that had fought against Germany during the war proved far more difficult. But even there, Bosch’s close personal ties had stood the test of time. One example is England, where one of the former managers of the Bosch Magneto Company in London, John Arthur Stevens, had founded his own company. In 1920, Stevens’s company started selling Bosch products in the United Kingdom. Despite the small volume, with the United Kingdom buying merely some 5 percent of all the magneto ignition devices produced, the move helped Bosch get its foot back in the door, and was crucial in the company's internationalization process. Nevertheless, selling German products on the British market was not easy, and the associate newspaper Bosch-Zünder often reported on anti-German prejudice in England. While the hatred was understandable after four years of wartime atrocities, the sentiments were also economically motivated by a desire to protect the domestic magneto ignition device industry. As a result, the competitor from Stuttgart served as a popular scapegoat in the national press. The situation was similar in France, where Fernand Péan became the agent for Bosch products in 1920.

International representatives’ meeting

In June 1920, Stevens and Péan could take encouragement from the first post-war sales conference. Twenty-eight representatives from 14 countries met at Bosch’s headquarters in Stuttgart. With a certain amount of pride, Bosch-Zünder wrote: “Save for a few exceptions, this was a reunion with all our old friends and agents – most of whom spent years prior to the war helping our name earn a fine reputation around the world.” Over the course of four busy days, the international representatives were briefed on pricing policy, sales planning, dealing with competitors, production capacities, and the latest technical innovations. In the years before the war, the concluding festivities had been one of the highlights of such meetings. In 1920, however, out of respect for the losses suffered during the armed conflict, there was no such celebration. Instead, the meeting ended with a dinner attended by Robert Bosch, who addressed the international representatives in a “serious yet optimistic speech.”

An international presence — along with global sales, manufacturing, and development networks — has always been a central element of Bosch’s corporate strategy. Internationalization helped Bosch overcome the aftermath of wars and crises. Back in 1932, the company founder Robert Bosch summed up the company’s clear commitment to international trade and globalization as follows: “After all the technological progress that has been made, our world has now become too small for any nation to consider shutting itself off from the others. Despite everything, interests are now so closely intertwined that the only possible form of economic activity is global.”

Author: Christine Siegel